Submitted by Victor on

CRIN’s collection of case studies illustrates how strategic litigation works in practice by asking the people involved about their experiences. By sharing these stories we hope to encourage advocates around the world to consider strategic litigation to challenge children's rights violations

Summary

Sentenced to death for a crime allegedly committed when he was just 14, the case of a Bangladeshi boy became the centre of a lengthy legal battle which ultimately led to mandatory executions being declared unconstitutional.

Background

Shukur Ali was 14 years old when he was arrested in connection with the rape and murder of a seven-year-old girl. At the time, the summer of 1999, Ali lived with his mother and elder sister in the slums of western Bangladesh’s Manikganj District.

The murder was described as “brutal and diabolical”, with the girl’s body found naked in Ali’s locked house with wounds on her leg and genitals. Later reports described how she had been “sexually assaulted to death”.

The victim had been left to play on a veranda but when her parents realised she had gone missing they began searching door to door throughout the neighbourhood. Upon finding the girl dead the people of the village tracked down Ali and brought him to the scene.

According to police reports he confessed to the crime, but later documents filed in his defence allege that the confession was made as a result of torture and was neither true nor voluntary.

Unable to afford legal assistance, Ali was appointed a defence lawyer by the state. At that time, defendants did not usually receive legal aid but, because of the severity of the punishment that would be handed down were he found guilty, Ali was entitled to free representation.

Ali could have been tried either under section 302 of the Penal Code, or under section 6(2) of the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan (Bishesh Bidhan) Ain 1995, a law designed to deter crimes against women and children.

If convicted of causing death after rape under the 1995 Ain the only punishment the court was allowed to hand down to Ali was death, while the Penal Code also allowed for a sentence of life imprisonment.

Despite having a lawyer, Ali’s initial trial was a sham, with serious errors noted in subsequent appeal judgments. In July 2001 Ali was found guilty, sentenced to death by hanging under the 1995 law and thrown into Dhaka Central Jail, a prison now plagued by allegations of corruption and mismanagement.

In addition to this, between the time when Ali was charged and sentenced the law was changed. In February 2000 life imprisonment was added as an alternative punishment for the crime he was convicted of, allowing judges some discretion where there were mitigating circumstances. However, the newly enacted law stated that cases brought or pending under the 1995 Ain, such as Ali’s, would be sentenced as if that law had never been repealed.

Appealing the sentence

Ali appealed against the conviction and the sentence, claiming that he was unlawfully detained and that there had been discrimination in his case, as he could have been tried under a different law for the same crimes, a law that would have allowed judges discretion in deciding his sentence on due to his age.

However, the decision was confirmed by the High Court Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh in a judgment handed down in February 2005. The judges dismissed his appeal, saying that the prosecution had proven the case at the time, despite the numerous problems with the case coming to light after it had finished.

First, the judge observed that, upon examining the evidence, there was “no reason to doubt that the condemned prisoner is barely a boy of 14 years of age at the time of occurrence and 16 years old at the time of trial of the case” and so, was a minor.

Ali should have been sentenced under a law aimed at juveniles to take account of his minor status, but was instead prosecuted under the harshest available law.

The same judgment also pointed out that had Ali been sentenced under section 302 of the Penal Code, which stipulates either a death sentence or life imprisonment for murder, his punishment would have been commuted to imprisonment for life because of his age. Because Ali was tried before a special tribunal on account of the brutality of the murder no such reduction was available.

Importantly, the judgment also revealed that the Deputy Attorney General had conceded that Ali was not developed enough to “commit fornication” at the time of the crime, despite the report of a medical officer confirming the victim had been raped.

“This is a case, which may be taken as ‘hard cases make bad laws’”, declared the judge. Recognising the failures of the initial trial he admitted that “a state defence lawyer who has not properly conducted the case has defended the condemned prisoner. There are [sic] neglect and laches in conducting the case on behalf of the condemned prisoner, which is also an extenuating circumstance to commute the sentence.”

Despite the numerous failings of the trial the appeals judge felt there could not be an exception. He continued: "With pangs and agony the High Court Division had no other alternative but to confirm the sentence in view of the fact that the prosecution has been able to prove the charge against the condemned prisoner beyond doubt.”

Concluding, the judge noted that the President of Bangladesh was able to grant pardons or commute any sentence and suggested that this might be a fit case for such a remedy.

Bringing the constitutional challenge

Not content with the outcome of the trial, Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) contacted Ali and discussed a plan to challenge the constitutionality of section 6(2) of the 1995 law he was convicted under, relating to mandatory death penalties.

One of the lawyers for Ali, Nazneen Nahar, explained that at the time the case was a cause of public outrage. Because the press coverage of the appeals had taken it as fact that Ali had committed the crime, he was demonised in the media for the rape and murder of a 7-year-old.

More experienced staff, particularly senior advocate M. I. Farooqui, did not believe the reports, having previously studied court documents explaining the circumstances surrounding the murder.

Nahar said: “When I first joined this case I asked ‘why are we here standing for this boy who committed this offence?’ Mr Farooqui asked me ‘do you think that he did it?’ Then I read all the documents and I found that this boy was not a criminal.

“People obviously blamed that boy, so people were not so happy after the decision. But in our appellate division case I think the procedure was found to not have been well followed,” she added.

In 2005 Farooqui’s law firm, M. I. Farooqui & Associates, filed a petition with the High Court Division of the Supreme Court on behalf of BLAST, arguing that the law Ali had been tried under was unconstitutional due to it only providing a single punishment for his alleged crime, violating the protection of the law and prohibition of cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishment established in Article 31 and Article 35 of Bangladesh’s Constitution.

The case was heard over the course of nine court sessions held throughout 2009, from February to July. By the end of this stage, Ali had been in jail for around ten years, awaiting his own death for most of that time. Ali’s sentence was repeatedly suspended during the case to allow appeals on his behalf, only adding to the feeling of uncertainty while he languished in prison.

Ali’s lawyers drew on legal precedent from across the Commonwealth, citing laws from India, Bangladesh, Malawi and also referenced judgments from the United States and teachings from the Qur’an.

Explaining why the law Ali had been sentenced under was void under the Constitution, Farooqui reasoned that as a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which prohibits arbitrary deprivation of life and liberty, the State could not allow the courts to be reduced to simply handing out a single penalty decided by the legislature.

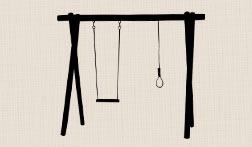

He claimed that by only allowing one punishment for the crimes listed in the 1995 law the courts were effectively reduced to a hangman’s noose, despite the fact that there may be mitigating circumstances in a case, with the simplest example in this case being the defendant’s age.

The judges agreed, ruling in March 2010, that without the ability to consider the particular circumstances of a case the courts became a “simple rubberstamp of the legislature” and that “where the appellant is not a habitual criminal or a man of violence, then it would be the duty of the court to take into account his character and antecedents in order to come to a just and proper decision.”

In response to arguments from the Attorney General that the constitutionality of the law was a non-issue the judges disagreed, stating that because the 2000 law stipulated cases initiated under the 1995 law were tried under the older rules, the execution of sentences under the 1995 law was still “very much a live issue”.

As a result, the judges found section 6(2) of the Nari-o-Shishu Nirjatan (Bishesh Bidhan) Ain, 1995 to be ultra vires, or beyond the authority of the law, declaring it unconstitutional. They also went further, saying that any law which provides only the death penalty could not be allowed under the Constitution.

Despite this admission they declared that, considering the crime he had been found guilty of, Ali’s detention could not be declared unlawful. The judges stayed Shukur Ali’s execution for two more months so that his lawyers could take his case to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court.

Ali’s final appeal

In their petition to the Appellate Division, Ali’s team questioned the High Court Division’s reasoning, claiming that if a law was declared void then a person imprisoned under it ought to be freed, and repeated their previous arguments about the need for clemency in the case due to the neglect in the conduct of Ali’s initial defence.

The judgment handed down by the Appellate Division blasted the legislators responsible for the law Ali was tried under and declared the related sections of the 1995 Ain and the 2000 Ain as void and unconstitutional.

Before reviewing Ali’s sentence, the judges reviewed the status of the death penalty in Bangladesh’s legal system. They claimed that social conditions and cultural values prevented them or the legislature from ending the death penalty entirely due to instances of women being killed for dowry, kidnapped for the purposes of sex trafficking and frequent acid attacks. They suggested that while other countries had outlawed death sentences they did not have similar problems and did not need such extreme deterrents for criminals.

They decided: “this country cannot risk the experiment of abolition of capital punishment. To protect the illiterate girls, women and children from the onslaught of greedy people, deterrent punishment should be retained.”

Defending the death penalty further the judgment explained the safeguards in place to protect people who may have been unfairly tried, as Ali allegedly was, including the provision of a defence lawyer for the accused, free copies of court documents and judgments, and the right to appeals that Ali had exhausted before reaching the stage he was at now.

For nearly 50 pages the judges demonstrated how similar cases had been dealt with in India, the United Kingdom and the United States before moving onto the provisions of the law in Bangladesh under the 1995 Ain. The judges noted that if several people were involved in a rape which caused death, the wording of the law would have them all executed, even if they were only guilty of aiding or abetting the crime.

“A law which is not consistent with notions of fairness and provides an irreversible penalty of death is repugnant to the concepts of human rights and values, and safety and security,” declared the judges.

“It appears from the above provisions to us that there was lack of contrivance in drafting the laws. If an enactment is sloppily drafted so that the text is verbose, confused, contradictory or incomplete, the court cannot insist on applying strict and exact standards of construction.”

Outcome

The bench noted that there was a “total absence of proper application of the legislative mind in promulgating those Ains,” and went on to declare sub-sections (2) and (4) of section 6 of the Ain, 1995, imposing the mandatory death penalty for causing death after rape, as void and unconstitutional.

The judges also voided sub-sections (2) and (3) of section 34 of the Ain of 2000, which stated that cases initiated under the 1995 law must be tried using that law. They held that cases such as Ali’s should be sentenced in accordance with the updated 2000 Ain, allowing for either a sentence of death or of life imprisonment.

Reviewing the merits of Ali’s case in this light the judges still found no cause to review his conviction, claiming that he had not been illegally detained, but because of the repeal of the provisions of the 1995 Ain his appeal was registered as allowed in part.

Finally, BLAST and Ali filed a new review petition with the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, asking for the commutation of Ali’s death sentence on the grounds of extenuating circumstances, that Ali was a minor at the time of the offence and the trial, and that there was negligence in conducting his defence during the initial trial.

Their petition noted that as the old law was declared unconstitutional and a different sentence was prescribed for cases where there were mitigating circumstances, Ali’s sentence was unduly harsh. On top of the original circumstances BLAST noted as a mitigating factor that Ali had now been imprisoned for 14 years, despite the obvious injustices of his trial and the numerous failures in his defence.

In August 2015 the Appellate Division commuted Ali’s death sentence to imprisonment for life “till natural death”, the first time Bangladesh’s Supreme Court had ever done so.

The final ruling was a long time coming for Ali, and although his case was a victory in a technical sense, he will never live free unless he is extended a Presidential pardon.

In the time since Ali was imprisoned, the law on criminal sentencing of children in Bangladesh has changed substantially, prohibiting the death penalty and life imprisonment for children, but still allowing children as young as nine to be held criminally responsible.

Nahar said that there was still more work to be done but that this case will act as the foundation of BLAST’s work to abolish the death penalty in Bangladesh completely. She explained: “We’re trying to reduce our use of capital punishment and hopefully we’ll soon file a writ petition against that punishment under our Constitution.

“It will take time, but we are trying to develop a constitutional case against the death penalty, not only for our children, but for everybody. If you cut off a life you cannot get it back.

“Everyone has the right to live.”

Further information

-

Read CRIN’s case summary of BLAST and another v. Bangladesh.

-

Find out more about strategic litigation.

-

See CRIN's country page on Bangladesh.

-

Read CRIN’s report on access to justice for children in Bangladesh.

-

Read about Bangladesh’s use of inhuman sentencing and why the death penalty and life imprisonment is a children’s rights violation.

CRIN’s collection of case studies illustrates how strategic litigation works in practice by asking the people involved about their experiences. By sharing these stories we hope to encourage advocates around the world to consider strategic litigation to challenge children's rights violations. For more information, please visit: https://www.crin.org/en/home/law/strategic-litigation/strategic-litigation-case-studies.